I use film terminology in acting classes: LS, MS, CU, XCU -- yes, wide shot ask for different (big) acting in contrast with the Closeup (see Film-North fo details).

Actor has to learn how to switch between the different modes of acting. Yes, my friends, you focus your audience attentions like the camera does it!

The rule of FRAMING is that the rest of the world is out of view, CUT OFF. If you want me to motice the changes on your face (CU), you can't move in space (MS or LS) -- I will miss it!

CU is often called "Head Shot" and MS - "Chest Shot": meaning that if you want to express "it" with your hands -- save it all for that "shot"!

Theatre Games:

"Act with hands only" (behind the door, make a dialogue with your hands only). "Feet Act"... or "heads only"...

Look at your monologue and design your movement -- CU, MS, LS (mark on Actor's Text). If "close up" -- what it will be -- eyes, mouth?

Cut everything else out!

Framing... or focusing.

Another name -- directing!

This chapter has several mini-chapters: one of them for actors.

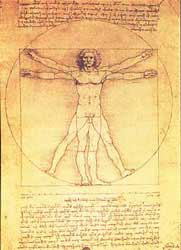

I call it -- Actor Body Meditation. Yes, homework and, yes, no less important than the wormups. The visualization of your own body --surface, musles, nerves, veins, bones. Layer by layer, part by part. The structures of the bodymachine. Actor must to put himself into a special mindset, without this attitude biomechanics become acrobatics. Do you know YOUR body? Did you studied it? Do you know how to do it?

CU (closeup shot)

MS (medium shot)

LS (long shot)

^ The Shrew Film Directing "showcase" ^

"If we observed a skilled worker in action we notice the following in his movements; (1) an absence of superfluous, unproductive movements; (2) rhythm; (3) the correct positioning of the body’s centre of gravity; (4) stability." [Meyerhold, 1922]

Summary

Kinoetics: Our Personal Body Language

Questions

"…the truth of human relationships and behaviour is best expressed not by words, but by gestures, steps, attitudes and poses." [Roose-Evans, 1989]Notes

New images from the Greek & Roman Times:

2004 & After

…Meyerhold's bio-mechanical actor said, "I make these movements because I know that when I make them what I want to do can most easily and directly be done." [1] "The Actor's Ways and Means", Michael Redgrave, William Heinemann Ltd, 1953

nonverbal communication by means of facial expessions, eye behavior, gestures, posture, and the like. Body language expresses emotions, feelings, and attitudes, sometimes even contradicting the messages conveyed by spoken language. Some nonverbal expressions are understood by people in all cultures; other expressions are particular to specific cultures. Kinesics, the scientific study of body language, was pioneered by the anthropologist Ray L. Birdwhistell, who wrote Introduction to Kinesics (1952).

Body Language is the unspoken communication that goes on in every Face-to-Face encounter with another human being. It tells you their true feelings towards you and how well your words are being received. Between 60-80% of our message is communicated through our Body Language, only 7-10% is attributable to the actual words of a conversation.

FAQ: A frequently asked question is, "What percent of our communication is nonverbal?" According to Kramer, "94% of our communication is nonverbal, Jerry" (Seinfeld, January 29, 1998). Kramer's estimate (like the statistics of anthropologist Ray Birdwhistell [65%; Knapp 1972] and of psychologist Albert Mehrabian [93%; 1971]) are hard to verify. But the proportion of our emotional communication that is expressed apart from words surely exceeds 99%. [ * ]

"To study language by listening only to utterances, say [University of Chicago professor of psychology and linguistics, David] McNeill and those who subscribe to his theories, is to miss as much as 75 percent of the meaning" (Mahany 1997:E-3).

THE SILENT COMMUNICATION

Chinese Emotion and Gesture

To acquire knowledge, one must study; but to acquire wisdom, one must observe. --Marilyn vos Savant Your body doesn't know how to lie!

* The process of sending and receiving wordless messages by means of facial expressions, gaze, gestures, postures, and tones of voice.

* Anthropologist Gregory Bateson has noted that our nonverbal communication is still evolving: "If . . . verbal language were in any sense an evolutionary replacement of communication by means of kinesics and paralanguage, we would expect the old, predominantly iconic systems to have undergone conspicuous decay. Clearly they have not. Rather, the kinesics of men have become richer and more complex, and paralanguage has blossomed side by side with the evolution of verbal language" (Bateson 1968:614).

* The first scientific study of nonverbal communication was published in 1872 by Charles Darwin in his book, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Since the mid-1800s thousands of research projects in archaeology, biology, cultural and physical anthropology, linguistics, primatology, psychology, psychiatry, and zoology have been completed, establishing a generally recognized corpus of nonverbal cues. Recent discoveries in neuroscience funded during the 1990-2000 "Decade of the Brain" have provided a clearer picture of what the unspoken signs in this corpus mean. Because we now know how the brain processes nonverbal cues, body language has come of age in the 21st Century as a science to help us understand what it means to be human.

* Neuro-notes. Nonverbal messages are so potent and compelling because they are processed in ancient brain centers located beneath the newer areas used for speech (see VERBAL CENTER). From paleocircuits in the spinal cord, brain stem, basal ganglia, and limbic system, nonverbal cues are produced and received below the level of conscious awareness (see NONVERBAL BRAIN). They give our days the "look" and "feel" we remember long after words have died away.

BODY MOVEMENT

I have always tried to render inner feelings through the mobility of the muscles . . . --Auguste RodinAs an actor, Jimmy was tremendously sensitive, what they used to call an instrument. You could see through his feelings. His body was very graphic; it was almost writhing in pain sometimes. He was very twisted, almost like a cripple or a spastic of some kind. --Elia Kazan, commenting on actor James Dean (Dalton 1984:53)

Concept. Any of several changes in the physical location, place, or position of the material parts of the human form (e.g., of the eyelids, hands, or shoulders).

Usage: The nonverbal brain expresses itself through diverse motions of our body parts (see, e.g., BODY LANGUAGE, GESTURE). That body movement is central to our expressiveness is reflected in the ancient Indo-European root, meue- ("mobile"), for the English word, emotion.

Anatomy. Our body consists of a jointed skeleton moved by muscles. Muscles also move our internal organs, the areas of skin around our face and neck, and our bodily hairs. (When we are frightened, e.g., stiff, tiny muscles stand our hairs on end.) The nonverbal brain gives voice to all its feelings, moods, and concepts through the contraction of muscles: without muscles to move its parts, our body would be nearly silent.

Anthropology. Stricken with a progressive spinal-cord illness, the late anthropologist, Robert F. Murphy described his personal journey into paralysis in his last book, The Body Silent. As he lost muscle control, Murphy noticed "curious shifts and nuances" in his social world (e.g., students ". . . often would touch my arm or shoulder lightly when taking leave of me, something they never did in my walking days, and I found this pleasant" [Murphy 1987:126]).

Confidence. "The physical confidence that he [Erik Weihenmayer, 33, the first blind climber to scale Mount Everest] projects has to do with having an athlete's awareness of how his body moves through space. Plenty of sighted people walk through life with less poise and grace than Erik, unsure of their steps, second-guessing every move" (Greenfeld 2001:57).

Media. In movies of the 1950s, such as Monkey Business (1952) and Jailhouse Rock (1957), motions of the pelvic girdles of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley, respectively, had a powerful influence on American popular culture.

Salesmanship. "Your walk, entering and exiting, should be brisk and businesslike, yes. But once you are in position, slow your arms and legs down" (Delmar 1984:48).

David B. Givens / Center for Nonverbal Studies

& thr blog

& thr blog

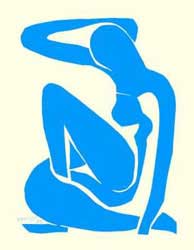

The other way to see it -- Matisse, or/and later Cubism. The phases of motion are combined in one static picture. (Compare the First "Blue Nude" aith the second). But the principle is the same -- the motion. The modernity was preparing us for "motion pictures"! The bottom line: you move, I watch. It could physical, emotional, intellectual movement. No movement, no show.

The other way to see it -- Matisse, or/and later Cubism. The phases of motion are combined in one static picture. (Compare the First "Blue Nude" aith the second). But the principle is the same -- the motion. The modernity was preparing us for "motion pictures"! The bottom line: you move, I watch. It could physical, emotional, intellectual movement. No movement, no show.